In the early 17th century, the universe was a neatly ordered place, at least according to the prevailing wisdom. Earth, humanity's home, stood motionless at the center, orbited by the Sun, Moon, planets, and a sphere of fixed stars. This geocentric model, rooted in the philosophies of Aristotle and Ptolemy and embraced by the Church, had held sway for over a millennium. Yet, on a cold January night in 1610, a middle-aged Italian polymath named Galileo Galilei turned a crude optical device towards the heavens, and in doing so, irrevocably shattered this cosmic order, setting himself on a collision course with the most powerful institution of his age.

The Spyglass Transformed: From Toy to Tool

The telescope was not Galileo's invention. Its origins trace back to Dutch spectacle makers, most notably Hans Lippershey, who in 1608 applied for a patent for a "kijker" or "looker." News of this intriguing spyglass, capable of making distant objects appear closer, quickly spread across Europe. Upon hearing the description, Galileo, a professor of mathematics at the University of Padua, immediately grasped its potential. With his keen understanding of optics and craftsmanship, he rapidly improved upon the initial designs, grinding his own lenses and perfecting the instrument. Within months, he had constructed a telescope that magnified objects twenty to thirty times, far superior to anything else available.

While others saw its military or mercantile applications, Galileo's genius lay in pointing it skyward. He was not merely an inventor; he was a visionary who understood that this new tool could unlock secrets hidden from humanity since time immemorial. His early observations were astonishing: the Moon, previously thought to be a perfect, unblemished sphere, revealed mountains, valleys, and craters, suggesting it was a world not unlike Earth. Venus displayed phases, just like the Moon, an observation that strongly supported the Copernican heliocentric model, as it could only be explained if Venus orbited the Sun.

A Universe Unveiled: The Medicean Stars

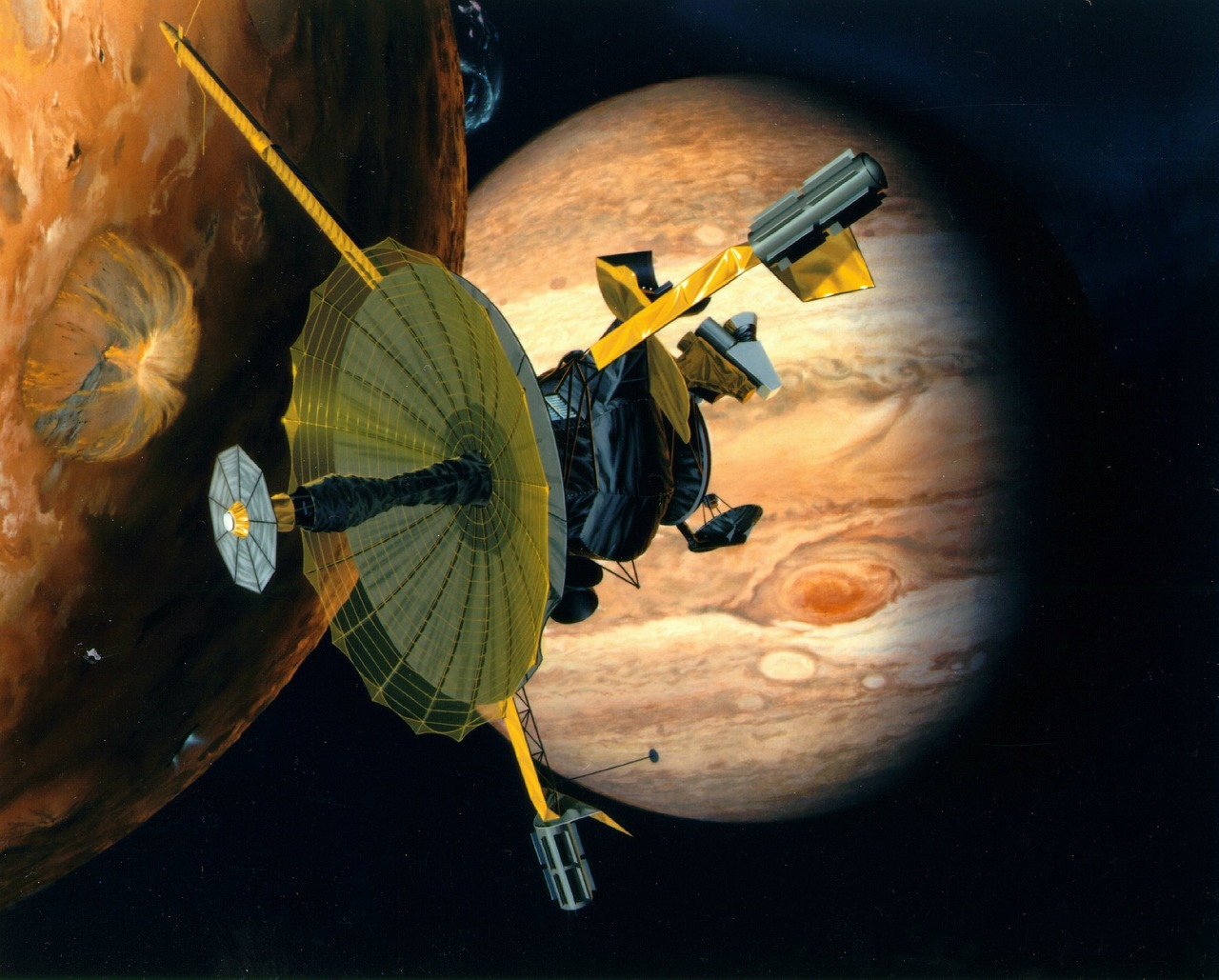

But it was his observations of Jupiter that delivered the most profound blow to the geocentric worldview. On January 7, 1610, Galileo noticed three small, star-like objects aligned near Jupiter. Over the next few nights, he meticulously tracked their movements. To his astonishment, these "stars" were not fixed but were clearly orbiting Jupiter itself. By January 13, he had identified a fourth such body. He had discovered Jupiter's four largest moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Galileo named them the "Medicean Stars" in honor of his patron, Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The implications of this discovery were revolutionary. Here, undeniably, was a celestial system where not everything revolved around the Earth. If moons could orbit Jupiter, why couldn't Earth and the other planets orbit the Sun? It was a miniature Copernican system writ large in the heavens, providing powerful, empirical evidence that challenged the very foundations of the Ptolemaic-Aristotelian cosmology.

The Earth Moves: Challenging Dogma

Galileo published his findings in March 1610 in a short treatise titled Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger). The book was an immediate sensation, met with both awe and skepticism. While some embraced the new discoveries, others, particularly within the Church and conservative academic circles, resisted fiercely. The idea of a moving Earth was not just a scientific question; it was a theological one. Scripture, interpreted literally, seemed to place Earth at the center of creation, and humanity as God's special focus. To suggest otherwise was to question divine authority and the very uniqueness of man's place in the universe.

The Copernican model, published in 1543, had been largely treated as a mathematical hypothesis, a clever way to calculate planetary positions, but not a physical reality. Galileo's observations, however, transformed it from a theoretical construct into an observable truth. He was not just proposing a new way to do calculations; he was asserting a new reality, one that contradicted centuries of established thought and religious doctrine.

The Storm Gathers: Inquisition and Condemnation

As Galileo's advocacy for heliocentrism grew more vocal, so did the opposition. Dominican friars and other conservative scholars began to denounce him from the pulpit. In 1616, the Holy Office of the Inquisition declared the Copernican doctrine "foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical inasmuch as it expressly contradicts the doctrines of Holy Scripture." Copernicus's book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, was placed on the Index of Prohibited Books, and Galileo was formally admonished not to "hold or defend" the heliocentric theory.

For a time, Galileo complied, focusing on other scientific pursuits. However, in 1632, emboldened by the election of his friend and admirer, Pope Urban VIII, he published his masterpiece, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Though written as a dialogue between a proponent of Copernicus and an Aristotelian, the book was an unambiguous and eloquent defense of heliocentrism. Crucially, the Pope felt personally ridiculed, believing that Galileo had put arguments he himself had made into the mouth of the simple-minded Aristotelian character, Simplicio.

The consequences were swift and severe. Galileo was summoned to Rome and tried by the Inquisition in 1633. Under threat of torture, the aging and infirm scientist was forced to recant his views, publicly abjuring his belief that the Earth moved. He was sentenced to house arrest for the remainder of his life, his works banned. Legend has it that after his recantation, Galileo muttered under his breath, "Eppur si muove" ("And yet it moves"), a defiant whisper against the forced suppression of truth.

A Legacy Beyond Retraction

Despite his personal suffering and the Church's attempts to silence him, Galileo's discoveries could not be unmade. The empirical evidence he presented laid the groundwork for future astronomers like Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, who would build upon his observations to formulate the laws of planetary motion and universal gravitation. The telescope, his "stargazer," had opened a window to a universe far grander and more complex than previously imagined, forever altering humanity's perception of its place within the cosmos.

Galileo's story remains a powerful testament to the enduring conflict between scientific observation and entrenched dogma. His courage in challenging the status quo, even at great personal cost, cemented his legacy as the "Father of Observational Astronomy" and a foundational figure in the Scientific Revolution. It took centuries for the Church to fully acknowledge its error, with Pope John Paul II formally rehabilitating Galileo in 1992. Today, the moons of Jupiter, still visible through even a modest telescope, stand as silent, luminous witnesses to the moment a simple lens transformed our understanding of the universe and ignited the fires of modern science.